|

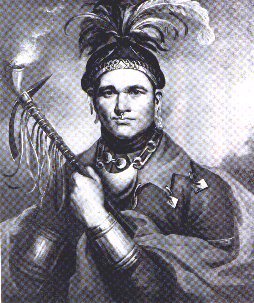

In reference to the personal appearance of Cornplanter at the close of his life, a writer in the Democratic Arch,(Venango Co.,) says:

"

I once saw the aged and venerable chief, and had an interesting

interview with him about a year and a half before his death. I thought

of many things when seated near him, beneath the wide spreading shade

of an old Sycamore, on the banks of the Allegheny - many things to ask

him - the scenes of the revolution, the generals that fought its

battles and conquered the Indians, his tribe, the Six Nations and

himself. He was constitutionally sedate, was never observed to smile,

much less to indulge in the 'luxury of a laugh.' When I saw him, he

estimated his age to be over 100 years. I think 103 was about his

reckoning of it. This would make him near 105 years old at the time I

speak of. Mr. John Struthers, of Ohio, told me, some years since, that

he had seen him near 50 years ago, and at that period he was about his

height - viz: 6 feet 1 inch. Time and hardship had made dreadful

impressions upon that ancient form. The chest was sunken, and his

shoulders were drawn forward, making the upper part of his body

resemble a trough. His limbs had lost their size and become crooked.

His feet, too, (for he had taken off his moccasins,) were deformed and

haggard by injury. I would say that most of the fingers on one hand

were useless; the sinews had been severed by a blow of the tomahawk or

scalping knife. How I longed to ask him what scene of blood and strife

had thus stamped the enduring evidence of its existence upon his

person! But to have done so would, in all probability, have put an end

to further conversation on any subject, the information desired would

certainly not have been received, and I had to forego my curiosity. He

had but one eye, and even the socket of the lost organ was hid by the

overhanging brow resting upon the high cheekbone. His remaining eye was

of the brightest and blackest hue. Never have I seen one, in young or

old, that equalled its brilliancy. Perhaps it had borrowed lustre from

the eternal darkness that rested on its neighboring orb. His ears had

been dressed in the Indian mode: all but the outside ring had been cut

away. On one ear this ring had been torn asunder near the top, and hung

down his neck like a useless rag. He had a full head of hair, white as

the 'driven snow,' which covered a head of ample dimensions and

admirable shape. His face was not swarthy; but this may be accounted

for from the fact, also, that he was but half Indian. He told me that

he had been at Franklin more than 80 years before the period of our

conversation, on his passage down the Ohio and Mississippi with the

warriors of his tribe, on some expedition against the Creeks and

Osages. He had long been a man of peace, and I believe his great

characteristics were humanity and truth. It is said that Brant and

Cornplanter were never friends after the massacre of Cherry Valley.

Some have alleged; because the Wyoming massacre was perpetuated by the

Senecas, that Cornplanter was there. Of the justice of this suspicion

there are many reasons for doubt. It is certain that he was not the

chief of the Senecas at that time: the name of the chief in that

expedition was Ge-en-quah-toh, or He-goes-in-the smoke. As he stood

before me, the ancient chief in ruins, how forcibly was I struck with

the truth of the beautiful figure of the old aboriginal chieftain, who,

in describing himself, said he was "like an aged hemlock dead at the top, and whose branches alone were green.' After

more than one hundred years of most varied life - of strife, of danger

and of peace - he at last slumbers in deep repose, on the banks of his

own beloved Allegheny."

|